Buried Alive

The fear of being buried alive is not an everyday topic of discussion. I have not really thought about it much, and being a funeral director for over 56 years, I cannot remember one instance of where a family voiced a concern to me about this. To my amazement, I discovered there is a medical term for this phobia or fear called “taphophobia” defined as “the abnormal fear of being buried alive because of incorrectly being pronounced dead.” I bet if you asked one of your friends what it means, they would have no idea.

Hollywood has successfully seized on this plot twisting 19th-century topic using one of humanity’s biggest fears of going to the grave while still breathing. There have been over 27 macabre movie thrillers, including 1962’s “The Premature Burial,” starring Ray Milland, the 1972 made-for-television horror thriller “The Screaming Woman,” starring Olivia de Havilland, and the 2007 film “Buried Alive,” starring Terence Jay. Bestselling authors have also used this subject and terrified us, including Stephen King in his 1993 buried-alive short story thriller “Dolan’s Cadillac” and author Peter James with his 1991 suspense novel “Twilight.”

I fondly remember as a kid in the 1950s going to the Aero Theater in Santa Monica, California, and I would cringe in my seat sitting next to my brother, Bill, our hands clutching a bag of popcorn – and my favorite box of candy corns in my shirt pocket.

Our eyes glued to the large screen watching the Saturday matinee horror film, gasping on every word the actors spoke along with the terrifying visual effects. We forgot at the moment, until our mother came to pick us up afterward, it was only Hollywood entertainment. However, turning the clock back to the 18th and early 19th century, it was not make-believe entertainment but actual everyday fears, experienced by societies around the world, of being buried alive.

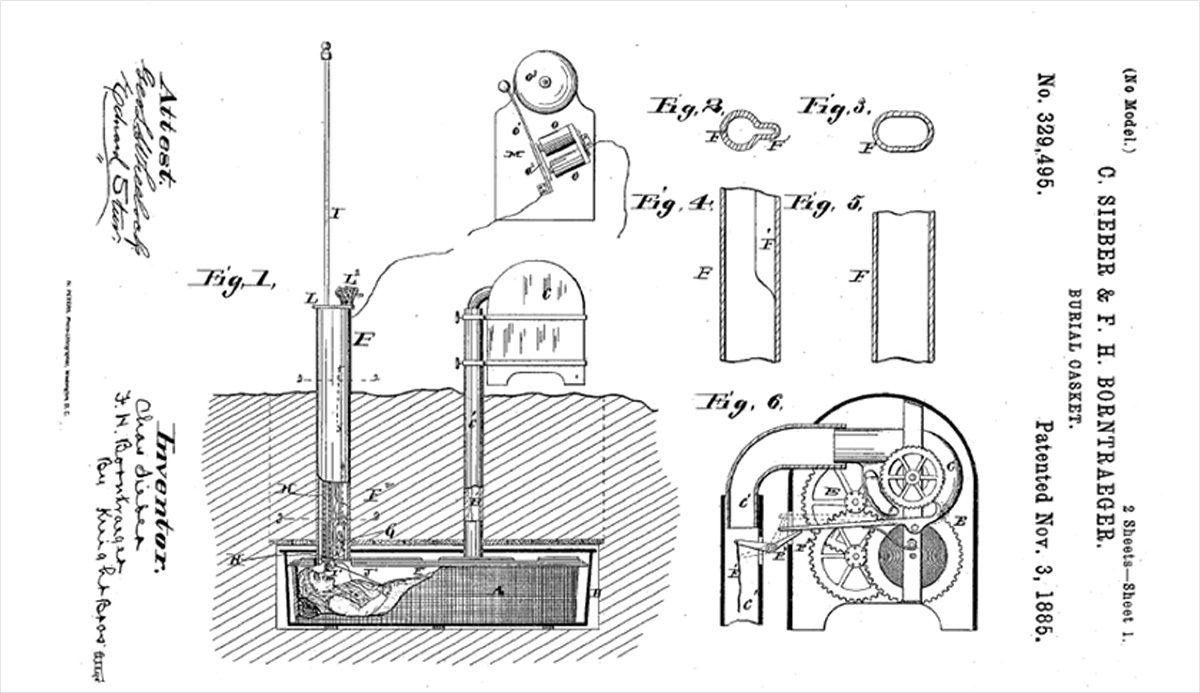

Burial Casket – Patent No. 329,495, dated Nov. 3, 1885. Applied for by Charles Sieler and Frederick Borntraeger, Waterloo, Iowa.

This fear of premature burial arose during the first half of the 19th century with hundreds of reports of medical personnel, with lack of training, pronouncing people dead when they were comatose or unconscious. The chances of this happening would be very slim. The world then was experiencing pandemics such as the Third Plague Pandemic in 1855, one of the deadliest in history; the Bubonic plague in 1899 that originated in Honolulu; and multiple cholera epidemics.

There were many literary works dealing with the fear of being buried alive, including three by Edgar Allan Poe: “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839), “Premature Burial” (1844) and “The Cask of Amontillado” (1846). Poe capitalized on the public’s fascination of this fear and was known for his tales of mysteries with macabre twists. To this day, his great works terrify millions.

Early newspaper publications reported cases of exhumed corpses that appear to have been accidentally buried alive. On Feb. 21, 1885, the New York Times gave a disturbing account of such a case. The victim was a man from Buncombe County, North Carolina, whose name was given as “Jenkins.” His body was found turned over onto its front inside the coffin, with much of his hair pulled out. Scratch marks were also visible on all sides of the coffin’s interior.

Another related story was reported in the Times Jan. 18, 1886, the victim of this case being described simply as a “girl named Collins” from Woodstock, Ontario. Her body lying in a coffin was described as being found with her knees tucked up under the body, and her burial shroud “torn into shreds.”

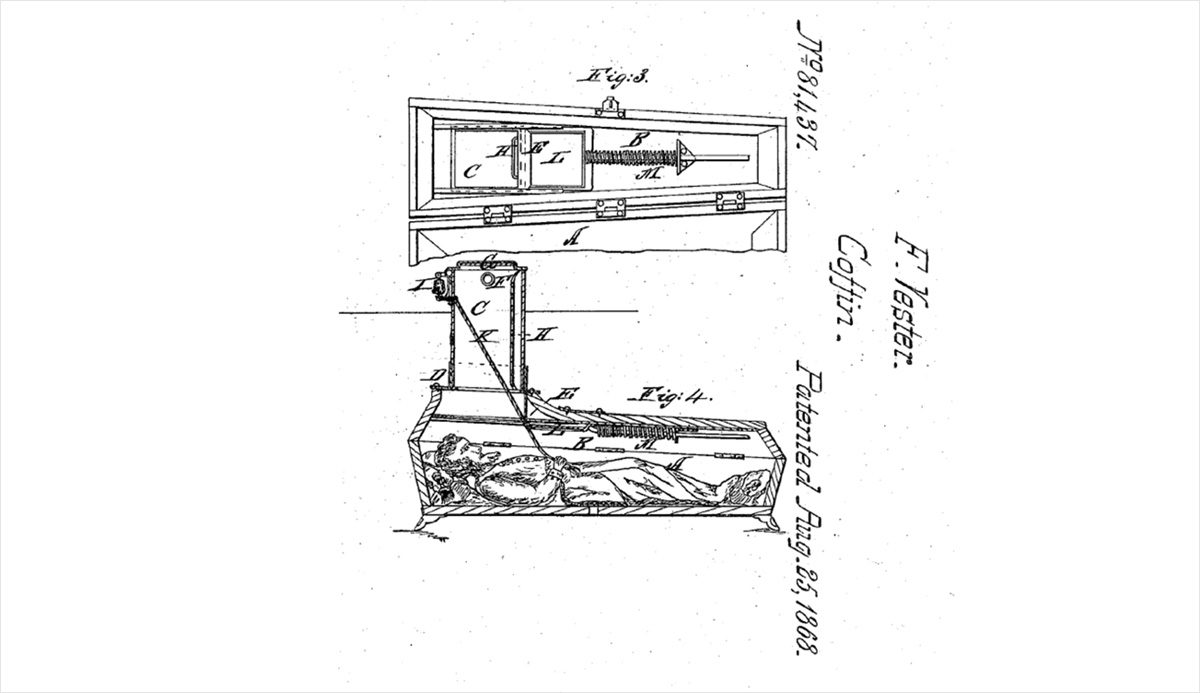

Improved Burial Case – Patent No. 81,437, dated Aug. 8, 1868. Applied for by Franz Vester, Newark, New Jersey.

George Washington, our first president, had this same fear of being buried alive. On his deathbed Dec. 14, 1799, trying to speak, he gave instructions not to place his body in a vault, but wait for three days after his death. This was his last known request.

In London in the early 1800s, bodies were taken to mortuaries and held there for days waiting for signs of putrefaction that were visible to be sure the person was dead. Hospitals, on the other hand, stored the dead in their wards and nurses watched over the bodies looking for putrefaction. To mask the smell in the hospital of rotting human flesh, flower arrangements were placed beside each bed.

With the growing fears of possibly being buried alive, a number of inventors, in order to alleviate the public concerns and trying to make some money along the way, used their imaginations and developed patented safety coffins for the unfortunate souls trapped alive. Their intent was noble and the end result was to have the person be able to communicate with the people aboveground by the use of wires, bells, flags, tubes and air tubes. They utilized in their designs spring load coffin lids and aboveground cemetery holding vault doors that can easily be activated to open by the slightest movement of the body.

The first safety coffin reportedly was constructed in 1792 for Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick before his death. He had a window installed to allow light in, an air tube to provide a supply of fresh air, and instead of having the lid nailed down, he had a lock fitted. In a special pocket of his shroud, he had two keys, one for the coffin lid and a second for the tomb door.

A German pastor in 1798 sug-gested that coffins should have a small trumpet-like tube attached. Each day the local priest could check the state of putrefaction of the corpse by sniffing the odors emanating from the tube. If no odor was detected or the priest heard cries for help, the coffin could be dug up and the occupant rescued. If this was fact or fiction, we will never know.

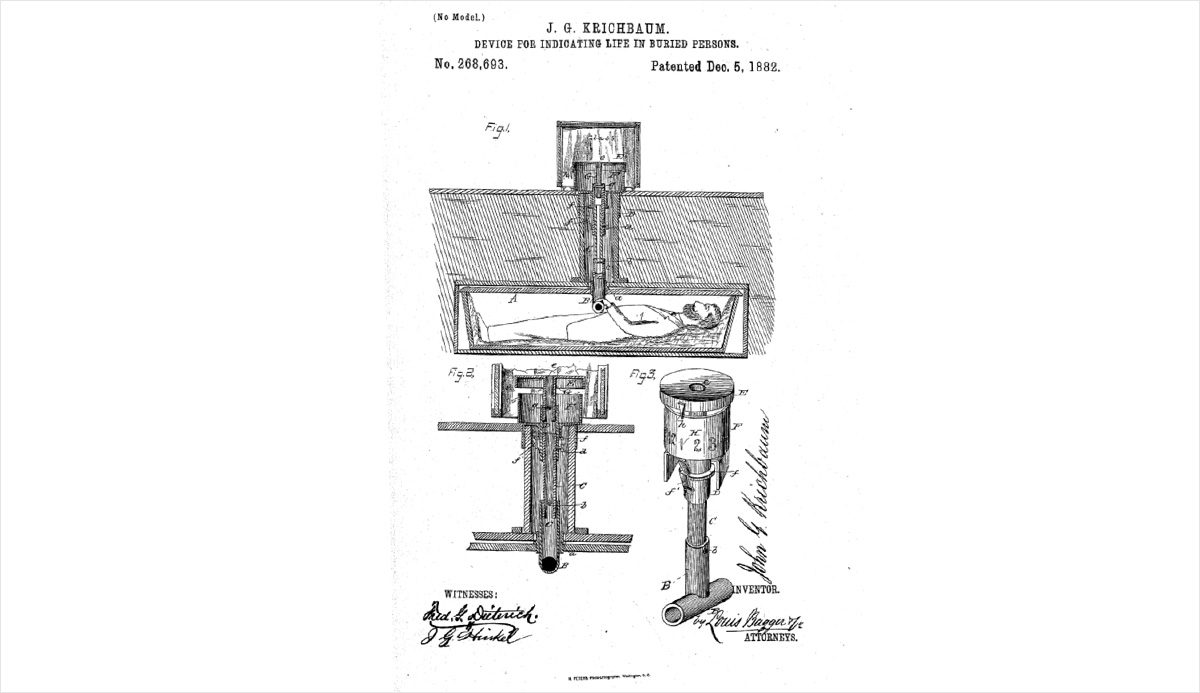

Devise for Indicating Life in Buried Persons – Patent No. 268,693. Dated Dec. 5,1882. Applied for by John G. Krichbaum, Youngstown, Ohio.

There were over 30 safety coffin designs patented in Germany alone in the early 1800s with the com-mon theme of the dead being able to communicate with the people aboveground and possibly save their life.

Let’s review some of the bizarre U.S. patents of the 19th century and you can make your own determination if the inventor had a good idea or were they a little eccentric? Most of the patents filed were designed to operate when the coffin and body were fully interred. No doubt, some of the designs must have had design flaws, which makes one wonder if the invention would have worked properly if used.

Burial Casket – Patent No. 329,495, dated Nov. 3, 1885. Applied for by Charles Sieler and Frederick Borntraeger, Waterloo, Iowa.

According to the patent, it states that the applicants have invented a certain new and useful improve-ment in Life-Guard Signals for people buried in a trance or before death, with the combination of a coffin the person is enabled to give a signal and to put in operation a fan or air-blast mechanism to force air through a large tube into the foot end of the coffin lid.

This is accomplished by a wire passed down a large tube running from the ground to the upper portion of the coffin and attached to the thumb of the person, which is then connected to a trigger and placed beneath a lever attaching to the clock-work mechanism of the fan.

According to the patent, “When the hand is moved, the exposed part of the wire will come in contact with the body, completing the circuit between the battery powered alarm and the ground to the body in the coffin,” – causing the alarm to sound. Air would also start flowing through a large tube into the coffin.

When activated, there is also a spring-loaded rod that will raise up, carrying feathers or other signals such as a flag to people above the surface of the ground – alerting them that movement of the person has occurred. A lamp can then be lowered down tube positioned over the face of the buried body and the person looking down through the tube can see the face of the body in the coffin to confirm life.

Improved Burial Case – Patent No. 81,437, dated Aug.8, 1868. Applied for by Franz Vester, Newark, New Jersey.

The patent explains that the body in the coffin has a cord attached to the hand, the cord is drawn through the square tube and is attached to a bell above the surface of the grave and the tube is attached to the lid of the coffin. The coffin is lowered into the grave and backfilled with dirt to the air-inlets. If the person in the coffin returns to life, he can decide to ascend from the coffin to the surface by a ladder; but, if too weak to ascend by ladder, he can pull the cord attached to his hand and ring the bell, giving the alarm for help, and thus saving himself. There is also a glass door on the coffin top, which may be easily raised or seen through for inspection of the person laying in the coffin. Should life be extinct, the square tube is removed and the sliding door is closed.

Devise for Indicating Life in Buried Persons – Patent No. 268,693, dated Dec. 5,1882. Applied for by John G. Krichbaum, Youngstown, Ohio.

If the person buried should come to life according to the patent, a T-shaped pipe passed into the coffin can be turned by the person using both hands – and an indicator above ground will show it’s been turned. The person can also push the pipe upward and push the glass cover off of the top of the grave and a supply of sufficient air will flow, allowing the person in the coffin to breathe freely until help arrives.

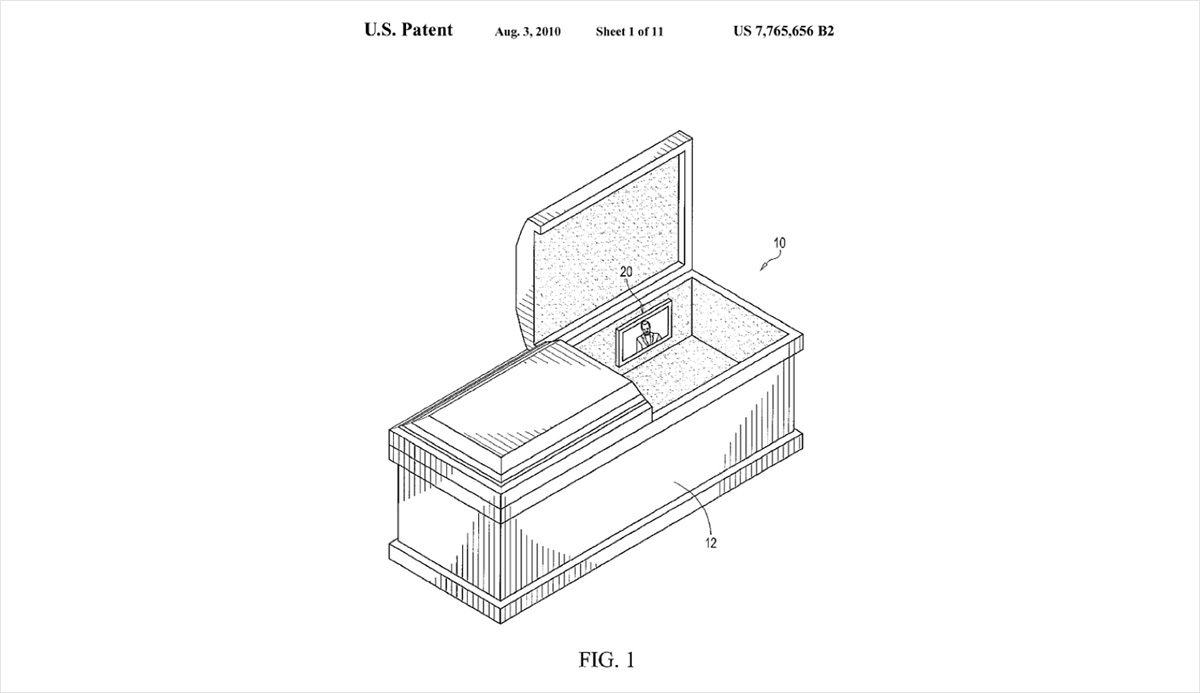

Apparatus and Method for Generating Post-Burial Audio Communication in a Burial Casket – Patent No. 7,765,656. Dated Aug. 3, 2010. Applied for by Jeff Dannenberg, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

To keep rain or other water from entering through the pipe, the box above the grave may be covered by a glass casing, so that the index indicator will still remain in full view of persons passing by. When the person has been buried a sufficiently long time to ensure the certainty of death, the aboveground apparatus may be removed by lifting the box and tube out of the grave, leaving the T-shaped handle in the coffin.

Today, inventors are taking a different twist on death – not focusing on being buried alive but on how the dead can communicate with the living using modern technology. For instance, there is a patent applied for by Jeff Dannenberg in 2010.

The description of the patent states the casket has an audio message system (20) containing audio and music files that are automatically played in accordance with a programmed schedule, thereby allowing the dead to communicate with the living. The system also allows for wireless updating of the recorded files, giving “surviving family members the ability to update, revise and edit stored audio files and pro-gramming after burial.”

Many Life Signs and Safety Coffin patents were filed over 150 years ago with the U.S. Patent Office, and we will never know the state of mind of the inventors or who they were. None of the patent designs filed sparked much interest with the public or even the funeral industry and there is no proof that any of the designs ever came to market or evidence that anyone was ever buried in a safety coffin, thus saving their life from pre-mature burial.

The story continues next month in American Funeral Director with unique funeral merchandise patents filed in the 1860s. These revolutionary coffin designs were apparently only a dream to the inventors as none ever came to market. From the collection of the National Museum of Funeral History will be photos of each of these intricate handcrafted patent models, which were required at the time of filing for a patent. •